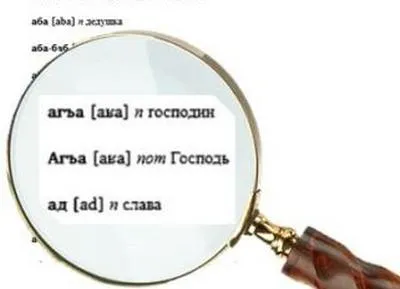

As I looked through the Tabasaran-Russian dictionary developed by Selina (a pseudonym), a Tabasaran linguist, a thought flashed through mind: “It must feel odd you to pray to God in Russian, where the word ad ‘hell’ sounds the same as the word ad ‘glory’ in your mother tongue.” Selina is the field-tester and local co-ordinator in IBT’s Tabasaran Bible translation project, and I also knew that she is a Christian believer. However, when I voiced my guess that she probably uses Tabasaran, and not Russian, in her church, she laughed merrily at my total ignorance. “Do you really think that there are so many Christians among my people that we could have opened a Tabasaran church?” she shrugged. “There are just two Christians on our translation team: the translator and myself. The rest of the team members are Muslims, as are the absolute majority of Tabasarans. Of course we have to attend a Russian-language church.”

The Tabasaran New Testament was published 10 years ago, in 2010, but there hasn’t been notable progress towards the full Bible translation since then. I inwardly wondered why, though I didn’t have enough courage to ask straightforwardly. However, I got Selina’s answer to my unformulated question almost from the very start of our talk. Along with other linguistic disciplines, Selina happens to specialize in toponyms and other names. This was lucky for me, as her scholarly and human interest coincided with the major problem in the Tabasaran Bible translation project. For this team of very talented and enthusiastic people who have been pursuing Bible translation into Tabasaran over the past many years, the names and titles of God appeared to be a real stumbling block. “The Tabasaran character is non-confrontational, we are milder than other Caucasian peoples, but we are very stubborn and incompliant,” shared Selina. ”Now, I actually consider stubbornness and obstinacy to be very positive and valuable character traits,” she added. “But due to them we were constantly having fervent discussions and fierce battles around key terms. It is only recently that we’ve agreed on a single approach as a team, and the language of our translations has started corresponding to a good literary standard. I really enjoy reading them now.”

“The names of God are a very important topic, indeed. For instance, Satan is Satan in all languages and traditions, but when we translate the names of God, we adapt the existing religious vocabulary in our language.” By this interesting remark Selina was pointing out a remarkable feature of her mother tongue. All Tabasaran nouns are divided into two classes: intelligent beings, and everything else. But Satan and the forces of evil happen to be in the same class with animals and inanimate nouns, not with God, angels and people. One can deduce a whole philosophy from such an unconventional religious worldview.

In contrast to many other Dagestanian translators and linguists whom I have met through IBT’s activities, Selina seems rather satisfied with the contemporary state of her mother tongue. Tabasaran is being taught at schools, and there is a newspaper, several TV programs and radio broadcasts in it. Although Selina’s own children, who are already adults, don’t speak Tabasaran as well as she does, her son sometimes initiates communication in it in a family circle. They also read and discuss Tabasaran Bible translations with him. Still, his knowledge of the language is not sufficient, so they switch to Russian time and again and have to make a conscious effort to return to Tabasaran. In addition, Selina admits that her son can’t pronounce especially difficult sounds. But this is nothing to be surprised at, since Tabasaran is in the Guinness Book of Records as one of the most difficult languages in the world to learn: it has from 44 to 52 cases, and about 50 consonant combinations! (But linguists say there are even more difficult languages in the Caucasus).

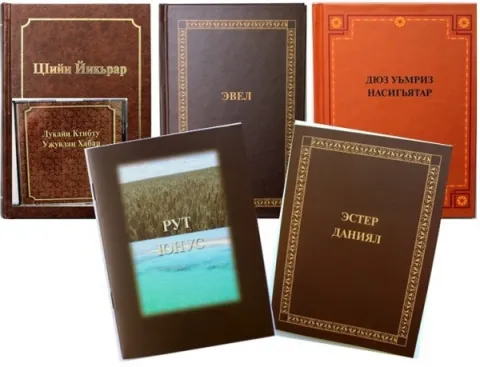

Nonetheless, to me Selina’s description of speaking Tabasaran with her son looked more like an exercise than as an act of natural communication in one’s mother tongue. Selina argued that this was only because her children grew up in the multi-lingual city of Makhachkala, whereas the real mother tongue speakers of Tabasaran live in villages. As mentioned above, Tabasarans are non-confrontational, and Muslim villagers never say anything aggressive against the Christian Bible when Selina brings newly translated Scripture portions to their local libraries. Selina feels that there is a good chance that Scripture translations, especially the OT portions, will find their way to Tabasaran hearts. “The OT Scripture portions that we have already published, Genesis and Proverbs in particular, are easier for an unprepared Muslim audience to understand,” she suggests, “because they deal with moral issues and respect for elders, things that are highly valued by our people. But I see how the Lord is working in people’s hearts through the NT translations too, as illustrated by our team. In the course of his work in the project, our NT translator has become a writer, and all his books are inspired by his Christian path. Another team member, the deceased philological editor of the NT, was a great Tabasaran poet. He remained Muslim, but his last volume of poetry was entitled ‘Crown of Thorns.’ The title speaks for itself. When I analyze the bulk of his works, I see how his poetic themes changed and transformed during his work on the NT.” After talking to Selina, I became interested in finding Russian translations of this deceased Tabasaran poet’s works on the Internet. The words I found were: “Poetry will live as long as there is mercy in the soul of at least one person.” Although strictly speaking, this wisdom may be traced back both to Christianity and Islam, I clearly heard the voice of a person who took the Gospel seriously.

One of the main signs for Selina that her native language will live and continue to develop is the existence of multilingual books that include both Tabasaran and parallel texts in other languages. For example, she greatly enjoys reading Tabasaran Scripture not in a book form, but in a Bible app for smartphones in parallel with Russian and English. Now Selina is working on an eight-language edition of a dictionary with Biblical vocabulary from Luke’s Gospel. Besides the Greek original, Russian and Tabasaran, the dictionary will include five other languages from the same language family: Agul, Udi, Tsakhur, Rutul and Lezgi. This dictionary will hopefully be published next year and may become a basis for similar dictionaries in other languages where Bible translation is in process.

We would greatly appreciate your financial assistance towards IBT projects. If you prefer to send your donation through a forwarding agent in the U.S. or Europe, please write to us and we'll provide the details of how this can be done.