There is an old Abkhaz legend about a widow. Her husband was killed, and she raised their three sons alone. When the sons grew up, the time came for them to avenge their murdered father according to their ancestral law. But who of them would become the avenger? The widow suggested casting lots to determine this. She would bake several pieces of flat bread and hide a small piece of wood in one of them. Whoever got this piece of wood would be the one to take revenge. However, the wise woman deliberately put the lot in the piece of bread that she herself received. Then she appealed to her sons to forgive their enemy. This old legend laid the foundation for a new tradition in Abkhaz culture. Every year, on the eve of the Lenten fast, when Orthodox Christians around the world celebrate Forgiveness Sunday by forgiving all the grievances inflicted upon them and asking for forgiveness from those whom they may have offended over the past year, the Abkhaz bring their unique custom into this celebration: all Abkhaz families, even those who profess Islam – and Muslims are also numerous among the Abkhazian population – bake cakes and recite the story of the wise widow and her forgiveness, unprecedented for a society dominated by blood feuds.

There is an old Abkhaz legend about a widow. Her husband was killed, and she raised their three sons alone. When the sons grew up, the time came for them to avenge their murdered father according to their ancestral law. But who of them would become the avenger? The widow suggested casting lots to determine this. She would bake several pieces of flat bread and hide a small piece of wood in one of them. Whoever got this piece of wood would be the one to take revenge. However, the wise woman deliberately put the lot in the piece of bread that she herself received. Then she appealed to her sons to forgive their enemy. This old legend laid the foundation for a new tradition in Abkhaz culture. Every year, on the eve of the Lenten fast, when Orthodox Christians around the world celebrate Forgiveness Sunday by forgiving all the grievances inflicted upon them and asking for forgiveness from those whom they may have offended over the past year, the Abkhaz bring their unique custom into this celebration: all Abkhaz families, even those who profess Islam – and Muslims are also numerous among the Abkhazian population – bake cakes and recite the story of the wise widow and her forgiveness, unprecedented for a society dominated by blood feuds.

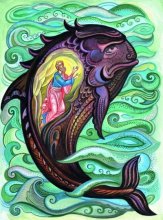

This legend was recounted to us by a longtime member of the Abkhaz Bible translation team Arda Ashuba. There is no doubt that such a folk tradition could take root only among a people permeated with Christian morals. And indeed, Christianity came to Abkhazia at the beginning of the 4th century. The Abkhaz writing system dates back to 1862, and 50 years later, in 1912, the first translation of the Four Gospels was published. As for the translation of the entire New Testament into the contemporary Abkhaz language, this was the achievement of just one person: the well-known Abkhaz poet, translator and philologist Mushni Lasuria. In 2005, Mushni Lasuria and IBT signed an agreement on further cooperation on translating the Bible into Abkhaz in accord with modern international scholarly standards. This means numerous exegetical checks and verification of the text against the original languages. Recently, a new exegetical checker joined the project, and is now taking his first steps in working with the Abkhaz text. Preparing an edition of Parables from Luke and drafting Jonah are the two immediate tasks on the Abkhaz translation team’s agenda.

This legend was recounted to us by a longtime member of the Abkhaz Bible translation team Arda Ashuba. There is no doubt that such a folk tradition could take root only among a people permeated with Christian morals. And indeed, Christianity came to Abkhazia at the beginning of the 4th century. The Abkhaz writing system dates back to 1862, and 50 years later, in 1912, the first translation of the Four Gospels was published. As for the translation of the entire New Testament into the contemporary Abkhaz language, this was the achievement of just one person: the well-known Abkhaz poet, translator and philologist Mushni Lasuria. In 2005, Mushni Lasuria and IBT signed an agreement on further cooperation on translating the Bible into Abkhaz in accord with modern international scholarly standards. This means numerous exegetical checks and verification of the text against the original languages. Recently, a new exegetical checker joined the project, and is now taking his first steps in working with the Abkhaz text. Preparing an edition of Parables from Luke and drafting Jonah are the two immediate tasks on the Abkhaz translation team’s agenda.

Arda, the translator, is a professional scholar: he is a professor in philology and the director of the Institute for Humanities Studies in Abkhazia. His experience with translation into Abkhaz is considerable and includes significant Christian texts. He also took part in editing a draft of the recently published translation of the Koran into the Abkhaz language, since, though a Christian himself, he respects the other religious tradition practiced by his people. In addition, he worked on translating the subtitles for the Jesus Film, which was recently released in the Abkhaz language. The idea to produce an Abkhaz version of the Jesus Film caused such an enthusiastic response that the actors who did the dubbing worked until 3 a.m. every day and completed the recording in ten days, even though most of them were not religious. Arda commented: “It was evidently God’s will that this film should be produced in Abkhaz: the actors bent over backwards to do this, and didn’t even ask for any payment – just for God's blessing.” The film was warmly received by the Abkhaz audience. People shared that they experienced the Gospel events in a much deeper fashion by watching the film in their native language than when they read the Gospels in Russian. A desire also arose to make a children’s version of the Jesus Film.

Arda has already produced translations of several short Old Testament books on his own, following his heart’s inner urge. During this work he noticed that “the Near Eastern way of thinking (including that of the Old Testament Jews) is very close to the Abkhaz mindset.” And he concluded that “the real translator is distinguished by seeking not the quantity of translated pages for which he will get paid, but the quality of each translated word. His task is to take hold of the life that vibrates in each word of Scripture so that it would be living, not dead, when it passes from the translator’s pen onto paper. This demands a lot of toil.”

After starting work with the new exegetical checker Arda expressed the essence of the Bible translation process in several vivid metaphors: “When flour arrives from the mill, it is not yet ready to knead dough from it. The flour must be sifted first, so that there are no lumps left. Only then will the dough turn out soft. Bible translation is like kneading dough from flour. When I am drafting the text, it’s like wholemeal flour. We do not want the Abkhaz text to resemble lumpy dough. When we search for the proper word together with the exegetical advisor, it’s like sifting the flour.” The exegete immediately picked up the comparison and clarified his role: “I can help with the sifting, but only the translator can say when the flour has reached the desired degree of softness.”

After starting work with the new exegetical checker Arda expressed the essence of the Bible translation process in several vivid metaphors: “When flour arrives from the mill, it is not yet ready to knead dough from it. The flour must be sifted first, so that there are no lumps left. Only then will the dough turn out soft. Bible translation is like kneading dough from flour. When I am drafting the text, it’s like wholemeal flour. We do not want the Abkhaz text to resemble lumpy dough. When we search for the proper word together with the exegetical advisor, it’s like sifting the flour.” The exegete immediately picked up the comparison and clarified his role: “I can help with the sifting, but only the translator can say when the flour has reached the desired degree of softness.”

Sometimes it is extremely difficult to remain true to the original text and at the same time make the translation sound natural. For example, the phrase that means “the Lord God” in the Abkhaz language is an established term literally meaning “the One who has power over us.” To say “my Lord,” however, would require changing the very form of the Abkhaz word into “the One who has power over me”, and this would sound as though we are not talking about the one true God, but about some kind of a lesser god, like that of the pagans. So what should the translator do if he needs to emphasize the personal attitude of a believer towards his Creator? How can he convey the words from the book of Jonah (2:1) that “Jonah prayed to the Lord his God?” The team has yet to solve this problem and many no less difficult ones, but the translator has already proclaimed his major principle of work: “I don’t want to artificially complicate the text for the reader. You can compare the translation process with buttoning a shirt. If the button is too large and the buttonhole too small, I cannot button my clothes properly. The word and its context are like a button and a buttonhole. They should fit each other. Or you can compare it with the shoeing process. I need to wear boots that are my size, otherwise I will have a hard time walking. In the same way, the reader will have difficulty understanding the passage if any words do not fit their context.”

Sometimes it is extremely difficult to remain true to the original text and at the same time make the translation sound natural. For example, the phrase that means “the Lord God” in the Abkhaz language is an established term literally meaning “the One who has power over us.” To say “my Lord,” however, would require changing the very form of the Abkhaz word into “the One who has power over me”, and this would sound as though we are not talking about the one true God, but about some kind of a lesser god, like that of the pagans. So what should the translator do if he needs to emphasize the personal attitude of a believer towards his Creator? How can he convey the words from the book of Jonah (2:1) that “Jonah prayed to the Lord his God?” The team has yet to solve this problem and many no less difficult ones, but the translator has already proclaimed his major principle of work: “I don’t want to artificially complicate the text for the reader. You can compare the translation process with buttoning a shirt. If the button is too large and the buttonhole too small, I cannot button my clothes properly. The word and its context are like a button and a buttonhole. They should fit each other. Or you can compare it with the shoeing process. I need to wear boots that are my size, otherwise I will have a hard time walking. In the same way, the reader will have difficulty understanding the passage if any words do not fit their context.”

The newly formed Abkhaz translation team is at the very beginning of a long journey, but their attitude to Bible translation is promising. “If I can be of any use to the Bible translation work, I will do whatever I can with great joy,” Arda says. “To tell you the truth, this is exactly the work that I would like to devote myself to. I want everybody to be able to praise the Lord in his/her mother tongue.”

We would greatly appreciate your financial assistance towards this project.

If you prefer to send your donation through a forwarding agent in the U.S. or Europe,

please write to us and we'll provide the details of how this can be done.

Share: